Overview

The Dreaming New Mexico project asked: What kind of trade policies do we want as State citizens or as foodshed locavores? What “tools” could make the dreams come true? More than any other part of this project, we found that few had asked these questions and that trade was entangled in many issues of morality and power. Our project is a humble beginning to give more thought to the relationships of local foodsheds, trade and moral values.

Not all trade is to everyone’s benefit. The consequences of freighting and free trade can hurt local rural economic life. From the local foodshed point of view, food production and trade that destroy rural economies are always questionable. For instance, New Mexico increasingly loses market share in the U.S. chile powder market. Compact, dried and dense food products like chile, onion or dried milk powders can be traded longer distances than bulky or perishable foods such as fresh green chiles or fluid milk. Chile for powder is also a labor-intensive crop: nations with cheap labor as far away as Peru, Ethiopia, and China can beat the New Mexico price. Such practices are often characterized as a “race to the bottom” for both environmental and labor standards.

The central dream of our project was connecting New Mexico to “sister foodsheds” around the world that can trade with a moral economy. Local foodshed producers, buyers, distributors and consumers can decide what is and isn’t acceptable to them. “Fair trade” (see our pamphlet) has many meanings: many groups hold differing values about the kind of commercial trade in which they are willing to participate. Most consumers and companies agree that exploitative child labor is unacceptable. Most want food safety rules to apply to their trading partners to avoid recent calamities such as pet foods with poisons, Mad Cow disease or leafy greens with E.coli. Many would like to know about gender equity and working conditions along the value chain. Still others desire foods that do not cause ecological destruction or are produced organically. To some, fair trade means reduced or eliminated trade barriers such as quotas, tariffs or restrictive sales licenses.

The two most frequent tools for building the sister foodshed trade system are product certification and trade association certification. The first certifies the product and value chain from farm to retailer; the second certifies that anything traded by the association follows specific agreed-upon rules. Both rely on truth of accountability, effective monitoring and transparency. Both rely on the positive power of giving market share to those companies and traders that follow specific ethical guidelines. In this dream, the State adopts the certification process and uses it for government purchases. Local foodsheds adopt the standard for their own production and sales in local groceries.

Global trade rules and foreign investment can preempt State goals such as preserving its iconic crop (chile) or improving rural economic development. When trade has multiple goals such as State food security and cultural identity, what should be binding? State policies and budgets, or international trade rules? New Mexico’s attitude toward food security and food sovereignty will impact the expansion of local food- shed markets and rural economic health over the next twenty years.

Why Trade?

Trade helps boost and stabilize the incomes of farmers and ranchers, allowing them to specialize in what they know their agro-ecoregion can best produce and market. Trade has a value chain of logistics and inputs that supports additional jobs and incomes while providing consumers with richly diverse choices. It can supply relatively fresh food, fish and meats in seasons where otherwise only canned, dried and processed foods would be available. Trade helps support better nutrition. Some products (chocolate, tequila, rice, ocean fish, coffee, tea) would not be part of New Mexico daily diets without trade. New Mexico buys almost 100% of its limes and mangoes from Mexico and probably over half its frozen broccoli/cauliflower and papayas.

Trade allows sellers to precisely appeal to customers. In-shell New Mexico pecans, for instance, are traded to Mexico. There, they are shelled and sorted. The jumbo pieces trade back to the U.S. for a premium market. The broken and small pieces stay in Mexico for their bakers and confectionery trade.

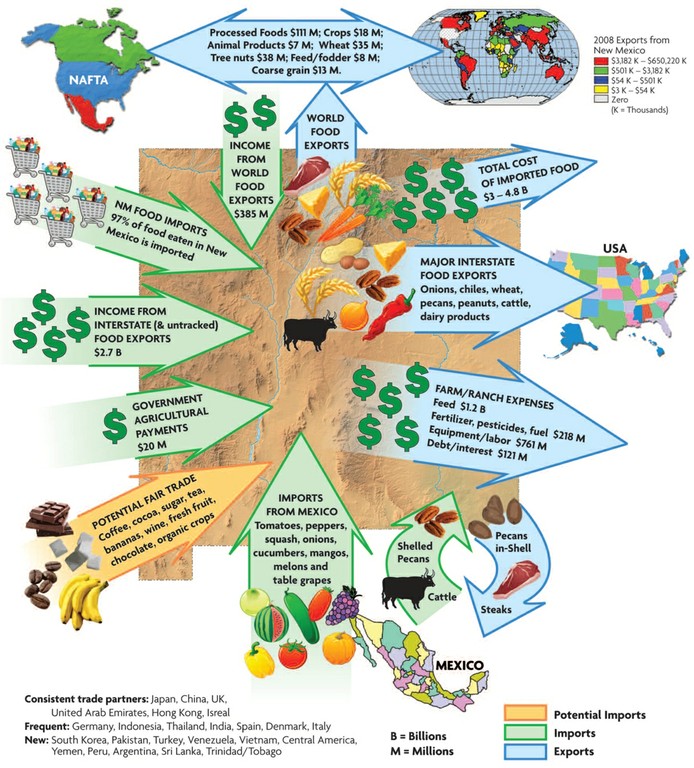

Map: Towards a Fair Trade State

Download Towards a Fair Trade State Map

Map shows the movement of food/ food products and food-related cash in and out of the State.

At bottom: The back-and-forth trade with Mexico of beef and pecans; and the major food imports from Mexico. Most of Mexico’s organic output comes to the U.S., including New Mexico.

On lower left are: Fair Trade foods coming into New Mexico.

On left side and top left: The income and food coming into New Mexico. Income includes: government payments from Washington; income from domestic and world exports; and food consumed in New Mexico. Top and right side of map shows exports of food and expenses related to food: exports of food to world and domestic markets; money leaving the State to purchase agrochemicals, labor, and machinery and cover debt; and the total cost to consumers of imported food.

Note: New Mexico spends $5 billion on food per year that is eaten in New Mexico. Because no agency tracks cash receipts for imported food and food products, estimates for imported food vary from $3 to $4.8 billion. In short, 97% of the actual food (by volume, weight) is estimated to be imports from outside the State.