Overview

Some believe water will be more important than energy in the near future. New Mexico uses about 75% of all its water for irrigation. Water disputes rage over irrigation between: New Mexico and other states, tribes and nations; urban growth and farmers; outdated water rights rules and modern understandings of the connections between groundwater and surface water; farmers and the state on issues such as who owns conserved water; and many more. Water and energy have become entangled with farming as a major energy need: pumping groundwater and treating wastewater to meet water qualities demanded by downstream users. Water needs for power plant cooling (coal, nuclear or solar thermal) conflict with irrigation needs. The energy to desalinate brackish waters will limit new water sources for New Mexico.

Water is “Don Divino,” the divine benefactor of sustenance. Native Americans have worshiped and danced for rain for thousands of years. When local foodsheds were the only foodsheds, water was life. Today there are great disharmonies between humans and water resources. Water can be viewed as a monetary commodity, an option for growth in the future that must be “banked” in the present, or for its intrinsic worth to all life (fish, trees, riparian birds). Water is central to defining a moral economy.

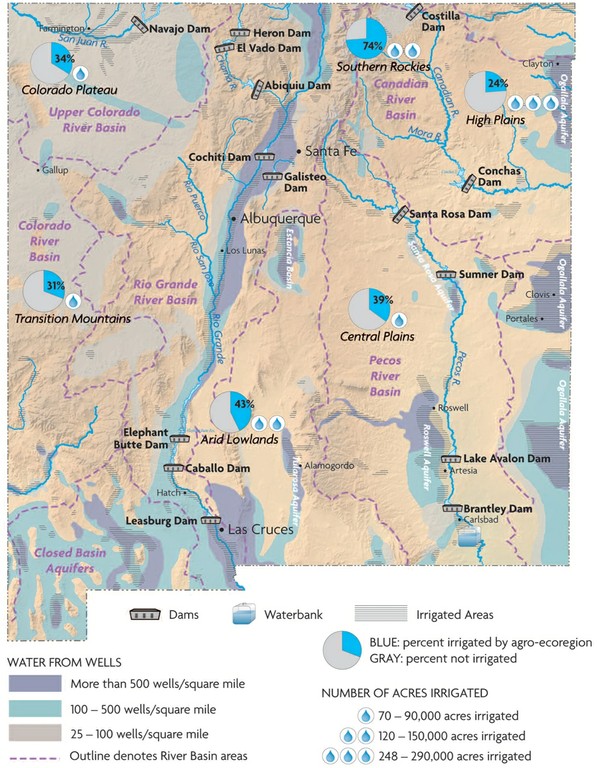

Map: New Mexico’s Lifeline

The map shows: major river basins, aquifers, dams, and irrigated areas. The circle graph shows irrigated vs. non-irrigated agriculture for each agro-ecoregion.

Agro-ecoregions: The High Plains relies on the Ogallala and Roswell aquifers as well as the Canadian River for irrigation. The Arid Lowlands irrigates from the lower Rio Grande and Pecos Rivers as well as the Tularosa Basin, closed basins and other lime- stone aquifers. The Central Plains relies on the Upper Pecos River and Santa Rosa aquifer. Although some local wells exist, the Southern Rockies depends on Rio Grande and Canadian surface waters; while the Colorado Plateau relies mostly on diversions from the San Juan River.

Complexity of Water Management

The boundaries of river basins:

- (a) groundwater basins

- (b) weather patterns (rainfall shown,

- (c) and agro-ecoregions

- (d) do not coincide.

The natural boundaries are not clear: ground and surface waters exchange waters; snow delays recharge and runoff compared to rain. This makes coordinated water management complex.

On top of these natural boundaries are governmental water district boundaries and more, with boundaries that have little to do with natural boundaries, decision making becomes even more complex.

Water Conservation

The best way to share water is to use only what you need and devise ways to save more. There are two different paths to water conservation: for the farm and for the waterworks system of the river basin. They have two different goals. Farmers need “growth” water, “leaching” water (to rid the land of salts) and “conveyance” water to move the water from river to the fields.

The hydro-basin system administrators need to meet compacts of downstream users — Texas and Mexico. Their goal is to minimize in-stream water depletions. each works with different tools. The water conservation dreams of New Mexico engineers include holding water in northern New Mexico as long as possible to reduce surface evaporation from the reservoirs. Some even suggest shutting down elephant Butte and replacing it with another dam near the Colorado River border. The river basin managers also think of storing the water in underground reservoirs rather than surface reservoirs.

Farmers may not be concerned about these waterworks changes as long as someone else pays for them and they receive the same volume of water on schedule. They try to finesse the right amount of application water to grow the highest yields. The State, for instance, subsidizes the conversion of flood irrigation to drip irrigation. The drip saves the farmer both water and money. However, water conservation rules and understandings make these simple conservation practices rare. If farmers conserve surface water and do not use it for four years, they forfeit it (use-it-or-lose-it). Farmers will not conserve under these rules.